Moran Lake Water Quality Study & Conceptual Restoration Plan

2.1 Regional Setting

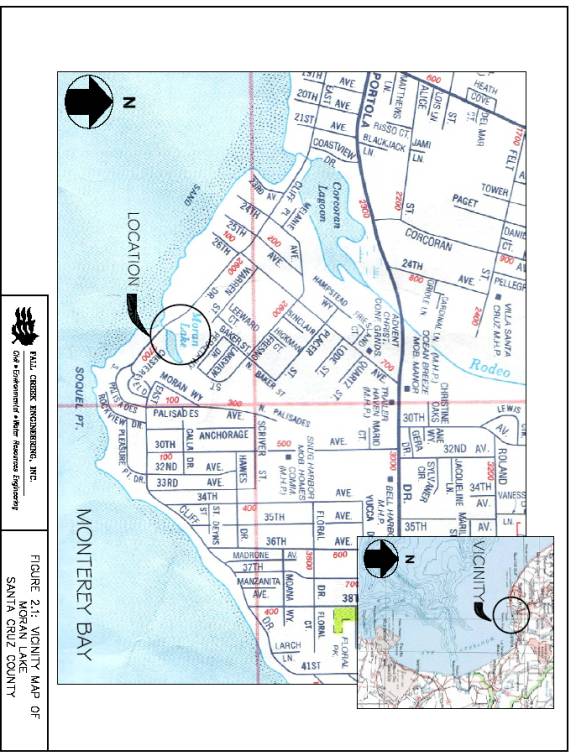

Moran Lake is a coastal lagoon that seasonally connects to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary in the Pacific Ocean. Moran Lake is located in the Live Oak Area of Santa Cruz County, California, as shown in Figure 2.1. The lake and adjacent land comprise Moran Lake County Park and the Lode Street Sanitation facility, and are the property of the County of Santa Cruz. The 9.2-acre park is located north of East Cliff Drive between Twenty-Sixth and Thirtieth Avenues, south of Portola Drive. Park facilities include restrooms, picnic tables, trails, beach access, and vegetated open space.

The Lode Street facility includes a wastewater pump station, sanitation district offices and surrounding eucalyptus groves. A plan and memorandum of understanding is presently under preparation for management of the eucalyptus and open space lands, with County Parks, Open Space and Cultural Services Department assuming future jurisdiction over these areas together with their existing management of Moran Lake Park lands.

2.2 Natural History

2.2.1 Geology

Moran Lake watershed is located between the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Cruz Mountains. The steep valleys in the mountains transition to relatively flat marine terrace and sea cliffs with narrow beaches parallel to the Monterey Bay. Urban development in the area is generally located in the area between the mountains and the ocean.

Surficial deposits in the area around the lake are described as lowest emergent coastal terrace deposits, originating from the Pliocene Age. The Purisima Sandstone Formation, also of Pliocene Age, underlies the terrace deposits beneath Moran Lake and extends beneath the Monterey Bay.

Two fault systems, the San Andreas fault and the Zayante fault, trend northwest through the Santa Cruz Mountains. Recent significant seismic activity in the vicinity of Moran Lake was recorded in 1989 on the San Andreas Fault, measuring 7.1 on the Richter Scale.

A 1980 environmental study of Moran Lake reports on the soils in the vicinity of the Lake. The bottom one to two feet of sediments in the lagoon are composed of a fine black silty-clay material, enriched with organic matter, with about 20-30 percent beach sands (Stern et.al., 1980). The terrain around Moran Lake, dominated by landfill materials, is composed of a variety of materials from coarse to fine sand, clay, silt, and small pieces of crushed granite rock (Stern et.al., 1980). During this investigation asphalt and concrete debris was also observed around the edge of the lagoon.

2.2.2 Hydrology

In the Moran Lake study area precipitation occurs almost entirely as rainfall. Precipitation rates on the coast range from 24 to 28 inches per year, with approximately 80 percent of the precipitation occurring between November and March (Hickey, 1968).

Groundwater in the vicinity of Moran Lake occurs within the sandstone beds of the Purisima Formation between the Zayante Fault and Monterey Bay. Drinking water is pumped from groundwater wells within the Live Oak area from the Purisima Formation. As freshwater is pumped from the Purisima Formation and if water levels are lowered, salt water can enter the freshwater aquifer (Hickey, 1968). Recent studies by the City of Santa Cruz Water Department indicate there is potential for salt water from coastal lagoons to enter groundwater.

The hydrologic response of surface waters in the Moran Lake watershed has been modified as a result of development and land use changes in the area. Increased impervious surfaces have decreased infiltration capacity and increased the volume of water entering Moran Lake, and its principal tributary Moran Creek. The decreased infiltration capacity has also increased the rate at which water moves through the watershed and enters these water bodies immediately after rainfall events. Impervious surfacing also decreases groundwater storage in the watershed, decreasing natural discharge to water bodies during dry months. Moran Creek and its smaller tributary channels have also been channelized, buried, or the riparian corridor reduced, causing impacts to the watershed hydrology.

2.2.3 Biology

Vegetation. Plant communities within the Moran Lake study area consist of annual grassland, disturbed ruderal, brackish wetland and open water. The upland areas of the lagoon have been colonized primarily by non-native plants, including some invasive species. (Species marked with an asterisk are non-native.) Dominant trees include blue gum eucalyptus* (Eucalyptus globulus), Monterey cypress* (Cupressus macrocarpa) and recent plantings of redwood (Sequoia sempervirens). Some black acacia* (Acacia melanoxylon) and arroyo willow (Salix lasiolepis) is also present in the upper park area near 30th Avenue. The majority of upland shrub and herbaceous species are also non-native. Dominant species include English ivy* (Hedera helix), Cape ivy* (Senecio mikanioides), French broom* (Genista monspessulana), wild radish* (Raphanus sativus), sea fig or ice plant* (Carpobrotus edule, C. chilense), wild mustard* (Brassica nigra), common plantain*(Plantago major), English plantain* (Plantago lanceoloata), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), mallow* (Malvia parviflora), nasturtium* (Tropaeollum majus), and curly dock* (Rumex crispus). Grass species are largely annual non-natives, including Italian ryegrass* (Lolium multiflorum), wild oat* (Avena fatua), barley* (Hordeum leporinum) and ripgut grass* (Bromus diandrus). A significant amount of invasive Himalayan blackberry* (Rubus discolor) is located along the upper streambanks near the Lode Street facility, and is preventing other riparian vegetation from becoming established.

Brackish wetland species are found on the lower lagoon slopes, in areas that are periodically inundated when Moran Lake is filled to capacity. Except for one plant, these species are native perennials adjusted to salt or brackish environments with differential tolerances for inundation. Pickleweed (Salicornia subterminalis) is found at the lowest zone, with alkali heath (Frankenia grandifolia), Jaumea (Jaumea carnosa), salt grass (Distichlis spicata) and fat hen (Atriplex patula) present at somewhat higher elevations, respectively. On the lower east lagoon bank, erosion has removed all wetland plants, while on the lower west side, the aforementioned non-native ice plant extends from the County Park parking lot to the lower Moran Lake shoreline, crowding out native upland and wetland species.

A somewhat disturbing trend is evident from a review of the 1980 Environmental Baseline Study (Stern et. al. 1980). The vegetation survey performed then identified some of the same non-natives found in 2004, but also included a significant number of native shrubs and herbaceous plants not in evidence today. Upland native shrubs identified in 1980 but not in 2004 include deerweed (Lotus scoparius), sky lupine (Lupinus nanus), bush lupine (Lupinus arboreus) and coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis). Herbaceous species included California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), coast hedge nettle (Stachys chamissonis), seaside dandelion (Agoseris apargioides) and loosestrife (Lythrum hyssopifolia). One native wetland species, Carex obnupta (slough sedge), was prevalent in 1980 but confined to one small area just south of the Lode Street facility in 2004. The brackish wetland species, Scirpus americanus (bulrush), was found in 12 locations on the lake edge in 1980 but was also absent in 2004. Conversely, the highly invasive non-natives, Himalayan blackberry, French broom, English ivy and Cape ivy were prevalent in 2004 but absent in 1980. Ice plant was found in several patches along the west lake shore in 1980, but did not cover extensive areas of the lagoon bank slope as it does today. Nearly all the dominant plant species in 2004 are non-native with a significant coverage of aggressive invasives.

Wildlife and Aquatic Invertebrates. Wildlife and in-lagoon benthic invertebrate surveys were not conducted as part of this study, although incidental observations of wildlife were made; however, wildlife and aquatic invertebrate populations are expected to be similar to those identified in 1980. Water birds associated with the lagoon include mallard ducks (Ana platyrhynchos), coots (Fulica americana), western gulls (Larus occidentalis), sanderlings (Crocethica alba), western sandpiper (Ereunetes mauri), egret (Cosmerodius albus) and great blue heron (Ardea herodias). Compared with Corcoran Lagoon and other productive coastal lagoons, water bird usage at Moran Lake is comparatively light, with relatively low density and diversity of species. This is probably due to the small size of Moran Lake and the low productivity of small fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Mammal and bird species in upland areas include common species typical of the urban environment. Gray squirrel, opossum, western harvest mouse, gopher and skunk were observed or trapped during the 1980 survey. Avian species included robins, mourning doves, starlings, swallows, song sparrow, white-crowned sparrow, red-winged blackbird, Brewer’s blackbird, Anna’s hummingbird and scrub jay.

Examination of plankton samples taken in May 1980 yielded calamoid corepods, oligochaetes (annelid worms), Capitellid polychaetes (worms) and four species of phytoplankton. From benthos sampling in Moran Lake mud sediments performed at the same time, oligochaetes, juvenile sand crabs (Emerita analoga), copepods and polychaetes were detected. Generally, the low numbers and diversity of invertebrates found in Moran Lake indicates an aquatic ecosystem that has relatively low productivity and is unable to support large numbers of fish and aquatic birds. Sampling of Moran Lake phytoplankton in 2003 (Swanson Hydrology 2004) showed a vastly different species’ composition when the lagoon was closed compared to results when it was open. This characteristic also indicates lack of a stable aquatic community that is probably due to extreme salinity variations under winter and summer conditions (see Water Quality section).

Special Status Species. Two special status species are known to occur at Moran Lake. The federal endangered tidewater goby (Eucyclogobius newberryi) has been observed in Moran Lake in the past (Smith 2002); however, the reconfiguration of the lagoon with harbor dredge spoils which removed backwater refuge areas, and annual runoff which empties the lagoon during winter months (see Figure 3.6) may have removed this species. Although no gobies, or other fish species were captured during Moran Lake seining in 1980, recolonization is possible from other nearby known localities such as Corcoran Lagoon and San Lorenzo River lagoon.

Tidewater goby is a small fish (~50mm) that inhabits low salinity coastal lagoons and lower reaches of coastal streams. Gobies have a short one to three year life cycle. Food sources include small crustaceans, aquatic insects, and mollusks including some benthos living in lagoon sediments. It requires backwater areas for long term survival, and threats to its existence include winter flooding, water diversions, water quality degradation from human, industrial and agricultural wastes and physical alterations to lagoons and marshes. The species has been extirpated from 56% of the localities it once occupied in southern, central and northern California.

The second species, monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a state species of special concern. The eucalyptus groves in Moran Lake County Park provide overwintering habitat for monarchs, and the Park is one of the larger and more important cluster sites in California. Destruction or alteration of overwintering sites is of concern for continued survival and conservation of the species. The eucalyptus grove surrounding the Lode Street facility has supported the largest cluster population of butterflies in the Park, although other Moran Lake eucalyptus groves support monarchs in early fall months (“autumnal sites”), or support butterflies as temporary refuge sites. Surrounding trees often function to provide a windbreak and create good microclimate conditions for butterfly roosts. Eucalyptus groves at Moran Lake Park have been adversely affected by resident tree-cutting or pruning, poor drainage and overcrowding. Increases in water and soil salinity is also a concern for future health of these trees. A Management Plan for Monarch Butterfly Habitat at Moran Lake County Park (Janecki et.al. 2002) has been prepared which provides information on monarch life history and recommendations for enhancement of monarch wintering habitat. An effort has been made to make recommendations in this water quality plan consistent with that document.

2.3 Historic and Present Watershed Boundaries

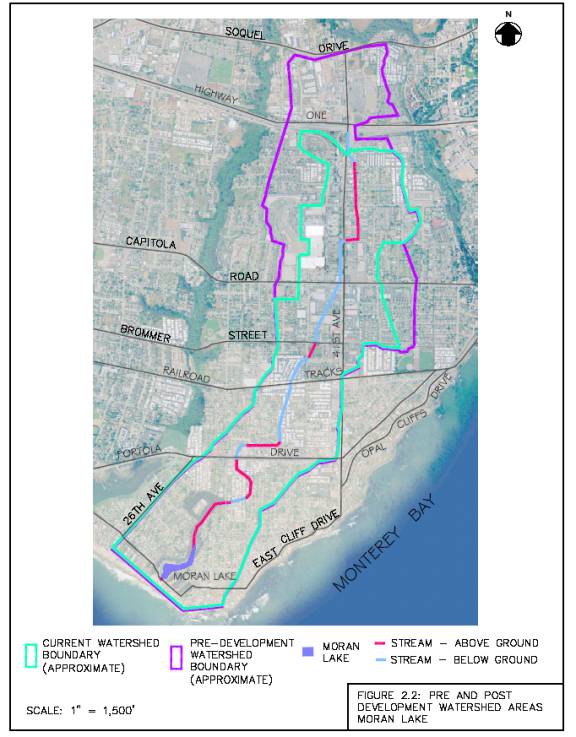

The conversion of lands from open grasslands to urban, commercial, and residential developments has altered drainage patterns within the Moran Lake watershed. Stormwater management and construction projects in the 1980s diverted approximately 180 acres from the Moran Lake watershed to either the Rodeo Gulch drainage system to the west, or Soquel Creek to the east. Figure 2.2 shows the approximate predevelopment boundary of the Moran Lake watershed, extending north of Highway 1, and the approximate boundary of the current watershed.

2.4 Jurisdictional Boundaries

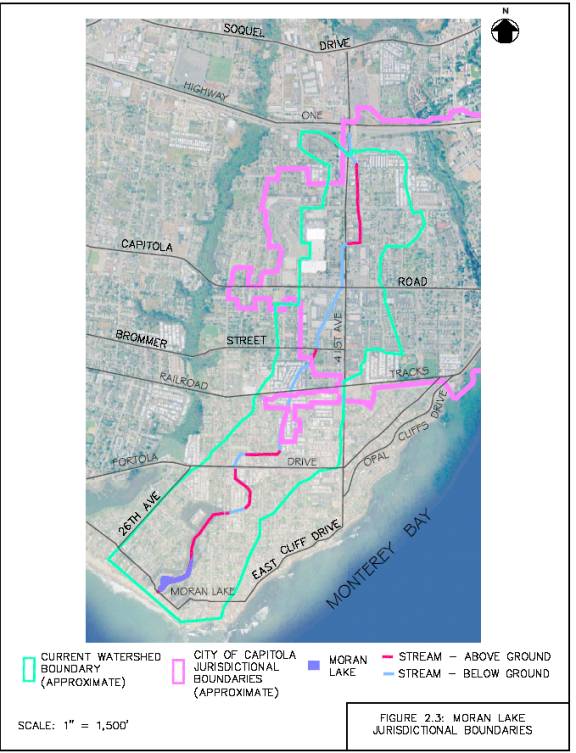

The Moran Lake Watershed lies within the County of Santa Cruz and the City of Capitola limits. Moran Lake is within the County of Santa Cruz and the upper portions of the Moran Lake watershed, beginning east of 35th Avenue and north of Portola Drive, are within the City of Capitola boundaries. The majority of the land within the watershed is privately owned, and landowner(s) or owner agents are responsible for maintenance of these lands. Public agencies, in this case within the City of Capitola and the County of Santa Cruz, are responsible for maintaining lands with public easements, public right-of-ways, and/or public lands (including roads). Figure 2.3 shows the current watershed boundary in relation to the City of Capitola jurisdictional boundary.

2.5 Land Use

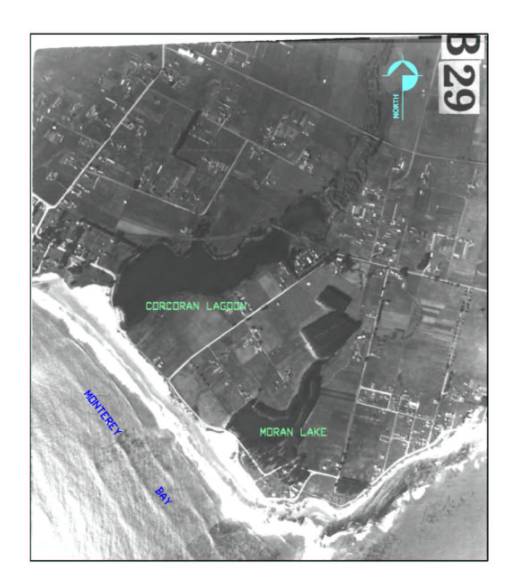

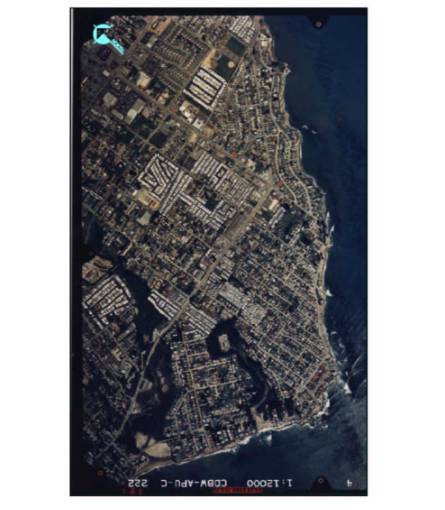

Land use activities in the Moran Lake watershed over the last century have evolved from primarily rural residential and agricultural to almost exclusively commercial, industrial, and urban residential land uses. As part of the land use changes impervious surface area has increased as urban hardscape has been introduced into the watershed to create roads, sidewalks, and parking lots. Aerial photographs taken of Moran Lake and the surrounding areas, beginning in 1931 depict these land use changes.

Figure 2.4 shows Moran Lake and the surrounding areas, including Corcoran Lagoon and Pleasure Point, in 1931. The area around the lake is mostly agricultural fields and rural residential developments. The existing eucalyptus trees have been planted adjacent to Moran Lake and at the current site of the Santa Cruz County Sanitation Lode Street Facility. The purpose of the eucalyptus plantings is unknown, and possible reasons include use for lumber, firewood, medicinal purposes, mosquito abatement, or as a wind break. The riparian corridor and channel of Moran Creek are visible in Figure 2.4 north of Moran Lake on the left side of the photograph.

Figure 2.4 Aerial photo of Moran Lake taken April 1,1931

Figure 2.5 Aerial photo of Moran Lake taken August 25, 1953

Figure 2.5 is an aerial photograph taken in 1953 of Moran Lake and the surrounding area. Most of the agricultural lands adjacent to the lagoon have been converted to residential developments since 1931. The site of the current Lode Street Facility has been developed and the riparian corridor and channel of Moran Creek remain visible north of Moran Lake.

Figure 2.6 Aerial photo of Moran Lake taken March 26, 1986

Figure 2.6 shows Moran Lake and the surrounding areas in 1986. The open space and agricultural lands surrounding the lagoon have been almost exclusively converted to residential and urban land uses. The extent of the Moran Creek riparian corridor has diminished, and in some locations it has disappeared where the creek has been placed underground in culverts.